AAC & Consent, Safety, and Dignity

This is a curated collection of information and resources related to prevention of abuse, harm, and infantilization of complex communicators and AAC users. We encourage you to explore and judge for yourself which to add to your toolbox.

These resources are for educational purposes. This is not an exhaustive list. Inclusion does not signify endorsement. Use of any information provided on this website is at your own risk, for which NWACS shall not be held liable.

Do you have a favorite resource that we missed? Send us an email to share!

NOTE: Speech-language pathologists and other professionals are mandatory reporters in Washington State. Caregivers paid to care for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities are also mandatory reporters. Mandatory reporters are required by law to immediately report the

abuse,

abandonment,

neglect, or

financial exploitation

of vulnerable adults. They must also report the abuse and neglect of children. This Care Provider Bulletin from the Washington State Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA) provides more information.

What are we talking about?

Disabled people are more than twice as likely to be the victim of a violent crime than their non-disabled peers. (1)

People with cognitive disabilities are the most likely to be the victims of violent crime. (1)

Rape or sexual assault against disabled people is only reported to the police ~19% of the time. (1)

It is estimated that more than half of all abuse of people with disabilities is done by family and peers. The other half is believed to be committed by service providers. (2)

It is scary to think about, but abuse, ableism, and infantilizing can happen in any environment.

Medical providers ask questions and talk with caregivers rather than the patient.

People use loud, higher-pitched, sing-songy voices to talk to a person in a wheelchair.

Staff remove swear words from an adult’s AAC device because they do not think the words are appropriate.

Disabled children are not taught about “tricky people” because adults think it will be too difficult for them to learn.

Disabled youth are not taught sex education because people assume they cannot/will not (should not) have sex. Or that they are unable to learn about sex and related issues.

These are just a few examples of the ableism and harm that disabled people regularly experience. This is what we are talking about.

Treating disabled teens and adults as a child or in a way that ignores their lived experience is called infantilizing.

Deciding a person is too disabled to learn or do something is ableist.

Abuse is most often from a familiar person. Especially where there is a power imbalance. People with disabilities (of any age) are vulnerable. They are vulnerable due to their disabilities. They are vulnerable due to isolation. They are vulnerable due to communication disabilities. They are even more vulnerable due to how they are raised and taught (or NOT taught). For many children with disabilities, there is just SO MUCH to do.

Families, teachers, and other providers might not think about teaching about consent.

Consent and related issues may keep getting pushed down the list as other things get prioritized.

But, too often children with disabilities are deemed “too __” (disabled, young, etc.) to learn about consent, boundaries, their body, sex, and other related topics.

Also, many adults feel uncomfortable talking and teaching about these topics. So they don’t. Or it feels so overwhelming! And they never start.

This is such an important issue! We have started this page to collect information and resources that might be useful.

Where do we start?

We need to start talking about and teaching these topics when children are young! And it doesn’t have to be complicated or time-consuming.

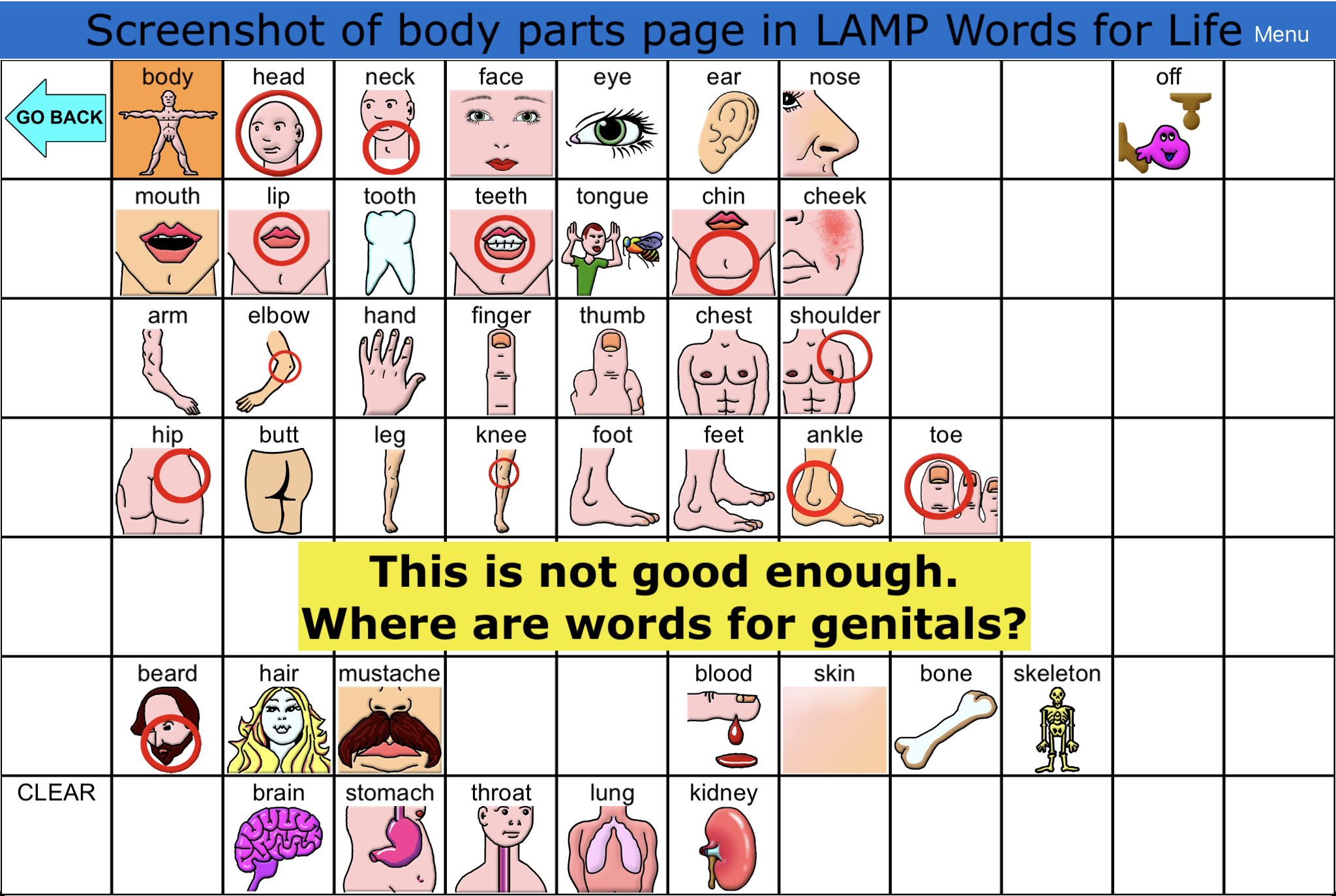

We talk about and teach the correct names for body parts (including genitalia). This can be worked into bath time, when toileting or changing, or when getting dressed. This can be worked into shared reading time by choosing books about bodies.

We make sure that all these body part labels are in their AAC device so we can model them and they have access to use them.

We talk about bodily autonomy. We teach them that it means they have a choice about what they do with (and what is done to) their body. We talk about how there are some things they need to do to keep themselves and others safe and healthy. But they can still have a say in how those things happen. We model saying “I’m not ready”, “I need a break” or making a request for something comforting. We talk about good versus bad touch.

We talk about consent. We teach them that consent means to agree. We teach that consent goes both ways. We have the choice to give or not give consent, but we also need to ask for consent from others. We talk about if a person uses power to get them to agree, it is not consent. We model giving a clear ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

We ask for consent before we provide physical help or physical care.

We make sure there are quick and easy messages in their AAC system to give or refuse consent. Often, this will mean needing to program these messages in. We model and practice using those messages.

We talk about boundaries. We teach them that a boundary is a limit. It is like a line between what they are comfortable with and what they are NOT comfortable with. We talk about how they can have different boundaries for different people or situations. We talk about how our boundaries can change.

We talk about secrets.

We talk about safety.

We talk about private versus public. We talk about how some actions, words, and topics are private. We talk about the difference between private and secret. We talk about choosing safe and trusted people to tell certain things.

We talk about different kinds of relationships and how they are different. Parents versus siblings versus extended family. Family versus friends versus caregivers. Romantic versus professional versus strangers. Acquaintances versus community helpers. We talk about healthy and unhealthy relationships. We teach signs of a healthy relationship: it feels safe and good, respect goes both directions, both people have bodily autonomy, feel happy, excited, confident, and that you can be your true self. We talk about signs of an unhealthy relationship: it feels bad and not safe, respect does not go both directions, one person tries to control the other, it makes you feel sad, anxious, scared.

We talk about trust. We talk about how most people are good, but some people build trust just to break it. We teach them that trust isn’t something a person earns and then has forever. That the person needs to work to keep our trust.

We talk about advocacy statements. We teach them that it is okay to say “No”. We talk about saying things like, “Stop, I don’t like that!”

We make sure that many advocacy statements are available in their AAC device. We model and practice using those statements.

We talk about emotions. All emotions - even the uncomfortable ones. We model talking about emotions. We model talking about the reason behind the emotion. We model problem-solving and responding to emotional situations.

Example of a self-advocacy page designed in Proloquo2go

We make sure the words they need to talk about emotions are in their AAC system. We practice using those words.

We teach them to go to their trusted, safe people to report when someone crosses a boundary. We model and practice how to do that.

We role-play. Practice in safe environments is so important.

What does this look like?

Here are some examples of what this might look like in practice:

We talk about consent. For example:

“Consent means you agree. Consent means ‘this is okay (to me).’ Not giving consent means you do NOT agree. It means ‘this is not okay (to me).”

We can then practice this in real life:

We ask: “Can I use your talker?” If the AAC user says or indicates “no”, we respond: “Okay. You did not give me consent. I will not use your talker.”

We ask: “Can I touch your hand to help you ___?” If the AAC user says or indicates “yes”, we respond: “I see (you nodding)/hear you (saying yes). You are giving me consent. I will touch your hand to help you ___.”

We talk about general safety. For example:

“Some people are safe. Some people are not safe. Some actions are safe. Some actions are not safe.”

We can then talk about real-life examples:

“Yumi is a family friend. They are a person we know. Most family and friends are safe people. A person you do not know is a stranger. Some strangers could be unsafe people. We don’t know if we can trust them until we get to know them. If you do not know if someone is a safe person to talk to, ask a trusted adult.”

Safe actions are doing things like:

looking both ways when you cross the street

not touching a hot stove

only using a knife when you need to cut food

Unsafe actions are doing things like:

running while holding scissors

swimming alone

not wearing a seatbelt

We talk about bodily autonomy and safety. For example:

“You get to decide who touches your body, where they touch you, when they touch you, and what reason they touch you. Not everyone is allowed to touch you. Only certain people are allowed to touch your private parts. If you need help with personal care, you can give consent to a caregiver to touch you in order to help you with your personal needs.

Mommy has familial love for Oma. If you have familial love for someone (someone who is, or is like, family), you can decide if they can give you a hug or a kiss.

Mommy has romantic love for Daddy. If you have a romantic relationship with someone, you can decide if they can hug or kiss you too. A hug or a kiss, or other actions, feel different with a family member than a romantic partner.”

We can then talk about real-life examples:

Aunt Mildred wants to give you a hug. If you do not want a hug from Aunt Mildred right now, you can say, “no.”

Your caregiver Jakob wants to help you change your shirt. If you do not want Jakob’s help, feel uncomfortable, or do not want to change your shirt right now, you can say, “no.”

Someone you have romantic feelings for wants to kiss you. If you feel nervous or not ready, feel uncomfortable, or do not want a kiss right now, you can say, “no.”

AAC is access to clear consent. AAC is access to setting and holding boundaries. AAC is access to all the words to talk about anything. AAC is access to report things that happen, including abuse. AAC is autonomy. AAC is safety.

Resources

**PLEASE NOTE** LINKS MAY CONTAIN LANGUAGE AND IMAGES THAT SOME PEOPLE MIGHT FIND OFFENSIVE.

Articles, Books, and Documents

AAC and Self-Advocacy (NWACS blog)

AAC Phrases for Medical Advocacy by Donnie TC Denome (mumblings from an autistic fairy blog)

AAC users need vocabulary to talk about sex, sexuality, and body parts by Donnie TC Denome (article on AssistiveWare blog)

Body Safety Education: A parents’ guide to protecting kids from sexual abuse

Body Smart, Body Safe: Talking with Young Children about their Bodies (A Mighty Girl blog)

Communication page I used to handle that invasive woman I met. by Mel Baggs (Ballastexistenz blog)

Communicative Competence: Emotional (NWACS blog)

Comprehensive Sex Education for Youth with Disabilities: A Call to Action from SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change

Dignity Remains Elusive for Many Disabled People - A Personal Perspective: I often feel like a charity case. by Hari Srinivasan (Psychology Today)

How do you symbolize intimacy? For many AAC programs, not particularly well. by Donnie TC Denome (mumblings from an autistic fairy blog)

Let’s Talk AAC: The Right to be Treated with Dignity and Addressed with Respect and Courtesy (Communication Right #13) (NWACS blog)

Sexual Health Education for Young People with Disabilities by Mary Beth Szydlowski (on eparent.com)

Sexuality for All Abilities: Teaching and Discussing Sexual Health in Special Education by Katie Thune and Molly Gage

Supported decision-making when you cannot speak, AssistiveWare blog

The Sexual Assault Epidemic No One Talks About by Joseph Shapiro (All Things Considered, NPR)

We Need to Talk About These #MeToos by Heather Kim Lanier (Star In Her Eye blog)

What Does Gender Have To Do with Presuming Competence? By Tuttleturtle (CommunicationFirst blog)

Books

Books written by or about disabled people that explore their lack of functional communication:

Ghost Boy: The Miraculous Escape of a Misdiagnosed Boy Trapped Inside His Own Body by Martin Pistorius

I Raise My Eyes to Say Yes: A Memoir by Ruth Sienkiewicz-Mercer and Steven B. Kaplan

Petey by Ben Mikaelsen

When We Pause by Kristin M. Rytter

Children’s books:

Websites

Bridge School Self-Determination Curriculum

Elevatus Training - offers an evidence and trauma informed curriculum on the topic of sexuality for people with developmental disabilities

Healthy Understanding of our Bodies from The Arc of Harrisonburg and Rockingham (VA) - a collection of videos, learning tools, and other resources about sexual health

Mad Hatter Wellness - offers a sex ed and health curriculum that educates and empowers people with intellectual disabilities and their support systems

Scarleteen - inclusive and supportive sexuality and relationships information for teens and emerging adults

Supporting Crime Victims with Disabilities online training toolkit from the Office for Victims of Crime and the Vera Institute of Justice

Podcasts

Lomah Disability podcast #167 - Slang, Swearing, Slurs...and AAC Censorship

Talking With Tech AAC Podcast episode - Rebecca Moles: How AAC Can Help Prevent Abuse and Neglect

Two Sides of the Spectrum podcast

Videos / Webinars

AAC and Self-Determination - Autonomy and Safety in Home/Community-based Services by Courtney Johnson (session from AAC in the Cloud 2023)

Am I muted?!? Fostering Effective Self-Advocacy in AAC Users by Jaime Lawson, Melonie Melton, Heather Patton, and Melissa Clark (session from AAC in the Cloud 2022)

Autism and Human Sexuality by Jack Duroc-Danner (2023, hosted by OHSU University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities)

Autonomy, Self-Determination, Dignity of Risk, and Harm Reduction for AAC User by Cole Sorensen & Donnie TC Denome (session from AAC in the Cloud 2021)

Consent in the Classroom - Why it’s essential to teach advocacy and boundaries at all age levels by Sarah Weber (session from AAC in the Cloud 2022)

Creating Low Tech AAC Supports to Improve Autonomy in Medical Appointments by Gemma White (session from AAC in the Cloud 2022)

Disability Justice and Latina/a/e/x Culture in the Sex Ed Classroom by Bianca Laureano (2023, hosted by OHSU University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities)

Ensuring Equitable Access to Health Care for AAC Users by Donnie TC Denome (session from AAC in the Cloud 2021)

Ethics & Neurodiversity: Let’s Talk About Sex a one-hour self-study course by Autistic OT Sarah Selvaggi-Hernandez on Learn-Play-Thrive (2023)

Keynote Address: Breaking Down Ableism to Unlock Possibilities by Yoo Sun Chung (Keynote from AAC in the Cloud 2021)

Let’s Talk about Sex! Education for Disabled Youth: Developing Comprehensive and Inclusive Sex Ed for Educators by Robin Wilson-Beattie (2023, hosted by OHSU University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities)

The Importance of Consent, Relationships, and Sexual Education for AAC Users by Donnie TC Denome (session from AAC in the Cloud 2022)

The Power of Core Vocabulary: Life Saving! Gail Van Tatenhove (YouTube video)

Uncensored AAC: Exploring AAC Access to Profanity and Slang webinar by Hali Strickler (USSAAC/ISAAC)

Where is the penis? Equipping AAC users to discuss personal and body safety by Gemma White (session from AAC in the Cloud 2022)

Materials and Other Resources

Abuse Communication Boards - The Centre for Augmentative and Alternative Communication at the University of Pretoria together with Dr Diane Bryan from Temple University in the United States developed communication boards for individuals with CCN who may have been a victim of abuse to report it.

Advocating for my AEM Workbook - Advocating For My Accessible Educational Materials (AEM) is a workbook designed for students to use as they begin to learn to advocate for the accommodations and accessibility features they need in their educational programs. It applies common self-advocacy principles to the needs of students who use AEM in their daily educational programs.

TalkingMats - TalkingMats are a tool to support people with communication disabilities to think about and express their feelings and views.

Selected References:

Bornman, Juan & Bryen, Diane. (2013). Social Validation of Vocabulary Selection: Ensuring Stakeholder Relevance. Augmentative and alternative communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985). 29. 10.3109/07434618.2013.784805.

(2) Breaking the Silence on Crime Victims with Disabilities. (2007). Join Statement by the National Council on Disability, Association of University Centers on Disabilities, and the National Center for Victims of Crime.

Bryen, D. N., Carey, A., & Frantz, B. (2003). Ending the silence: Adults who use augmentative communication and their experiences as victims of crimes. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 19(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/0743461031000080265

Collier, Barbara & McGhie-Richmond, Donna & Odette, Fran & Pyne, Jake. (2006). Reducing the risk of sexual abuse for people who use augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and alternative communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985). 22. 62-75. 10.1080/07434610500387490.

Cossar, J., Brandon, M., Bailey, S., Belderson, P., Biggart, L., & Sharpe, D. (2013). It takes a lot to build trust. Recognition and telling: developing earlier routes to help for children and young people. Office of the Children’s Commission, UK

(1) Crime Against Persons with Disabilities, 2009-2019 - Statistical Tables

Epstein, Robert & Bock, Sara & Drew, Megan & Scandalis, Zoë. (2022). Infantilization across the life span: A large-scale internet study suggests that emotional abuse is especially damaging. Motivation and Emotion. 47. 1-27. 10.1007/s11031-022-09989-4

Togher, Leanne & Balandin, Susan & Young, Katherine & Given, Fiona & Canty, Michael. (2006). Development of a Communication Training Program to Improve Access to Legal Services for People With Complex Communication Needs. Topics in Language Disorders. 26. 199-209. 10.1097/00011363-200607000-00004.